Stay informed with free updates

Simply log in to Artificial intelligence myFT summary — delivered straight to your inbox.

The writer is a novelist

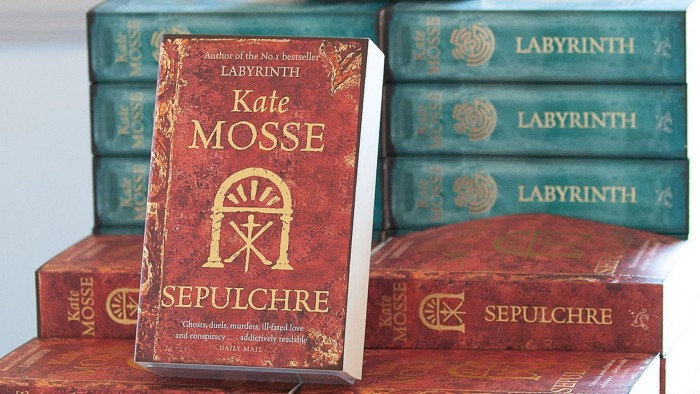

In 1989, we bought a small house in the shadow of the medieval city walls of Carcassonne. It was the beginning of my love affair with Languedoc — the history, the mysterious mysteries hidden in the landscape, the endless blue sky, the light over the mountains at dusk. It would inspire my first historical adventure novel, Labyrinthwhich will be translated into 38 languages and sold in more than 40 countries. Its global success is the reason I was able to quit my day job and become a full-time writer.

Imagine my horror, therefore, when I discovered that those 15 years of dreaming, researching, planning, writing, copying, editing, visiting libraries and archives, translating Occitan texts, searching for original 13th-century documents, becoming an expert on Catharism, apparently counted for nothing. Labyrinth is just one of several of my novels that he scratched Meta’s big language model. This was done without my consent, without compensation, without even notice. This is theft.

Artificial intelligence and its possibilities excite me. Using technology to improve, develop, experiment and innovate is part of every artist’s toolbox. We need time to create and, potentially, artificial intelligence can give us the space to do the things we love. But intellectual property theft is an attack on creativity and copyright and will undermine Britain’s world-leading creative economy. The time has come to unite and act.

It’s been a busy month in parliament for AI. On December 3, the Authors’ Licensing and Collecting Society published the report “Brave New World?” at the meeting of the All-Party Parliamentary Group of Writers. This survey of some 13,500 authors’ views on artificial intelligence threw a hand grenade into the one-sided debate about illegal scraping and indexing of copyrighted works and the misconceptions surrounding it.

On 9 December, Baroness Beeban Kidron gathered creators to discuss three proposed amendments to the Data (Use and Access) Bill currently going through Parliament, which would make UK copyright law enforceable in the age of generative artificial intelligence.

It comes ahead of a government consultation on how to boost cross-sector trust, ensuring AI developers give rights holders greater clarity about how their material is being used. So far so good. Except, when the consultation framework was revealed, it became clear that it was an attempt to fatally weaken UK copyright law in the name of “progress” by suggesting that creators and rights holders should “opt out” of their work being used for AI training.

When the House of Lords debated Kidron’s amendments this week, peers were united in their disdain for the government’s plans, with Kidron remarking: “The government has sold the creative industries down the river.”

AI companies portray creators as those who are against change. We are not. Every artist I know is already involved in artificial intelligence in one way or another. But a distinction needs to be made between AI that can be used in brilliant ways – for example, medical diagnosis – and the foundation of the AI model, where companies essentially steal the work of creatives for their own profit. We must not forget that AI companies rely on creators to build their models. Without a strong copyright law that ensures creators earn a living, AI companies will lack the high-quality materials that are critical to their future growth.

The UK has one of the most successful, innovative and profitable creative industries in the world, worth around £108 billion a year. The publishing industry alone contributes £11 billion each year and has the potential to grow by another £5.6 billion over the next decade. It supports 84,000 jobs and leads the world in publishing exports, with growth forecast at 20 percent by 2033. In the film industry, 70 percent of the 20 highest-grossing films in 2023 were based on books.

One of the reasons for this global success is that we have strong and fair copyright laws. The United Kingdom was a pioneer in this. The Statute of Anne, passed in 1710, was intended to encourage learning and support the book trade, creating a framework in which writers who authored works retained full rights, thus prohibiting publishers from reproducing works without permission or payment.

The government will undermine this robust and fair system if it pursues an opt-out – or “entitlement” in the new parlance – instead of an opt-in model. Why should we writers take on the burden of preventing AI companies from stealing our work? If the producer wants to make a movie, or a radio show, or a theater play out of it, contact us and we’ll make an agreement. Although the technology is new and under development, the principle is the same. AI is no different. It’s not just about fairness or wrongdoing, it’s about economic growth. If creatives have to spend time trying to find AI companies to stop our work from being stolen, we’ll have less time to work. This in turn will shrink our world-beating creative industries and hurt growth.

I fully support the government in its determination to seize the future and be a world leader in artificial intelligence innovation. More than sixty years ago, at the Labor Party conference in 1963, Harold Wilson spoke of the “white heat of the technological revolution” and the “university in the air”. This Labor government is following those forward steps. But weakening copyright is not the way to do it. Putting the burden on authors and other creators to opt out is not the way to do it. Without original work, there is nothing.