Take a look at the list of the 10 most valuable companies traded on the US stock market and something immediately jumps out at you. Nine companies make up the coolest and most exclusive club in the business world, led by glamorous tech companies Apple (no. 1) i Nvidia (No. 2), together with Microsoft, Alphabetand more. And then—there it is Berkshire Hathaway. As they used to sing on Sesame Street, one of these things is not like the others. It’s like seeing a typewriter company on a list of popular IPOs. Who let Berkshire walk the velvet rope? He owns a company called Acme Brick, for God’s sake. Its website does not appear to have changed much since about 1998. The CEO is 94 years old. But its market cap soared above $1 trillion a few months ago without anyone noticing, and now it’s just below Tesla and above Taiwan Semiconductor.

So what does it give? The deeper we delve into the bizarre Berkshire anomaly, the more improbable it seems and the more valuable the explanations. The company is literally in a class of its own. It’s not a tech company, but its market cap dwarfs that of every other non-tech company by such a wide margin that it doesn’t seem like any of them are; his runner-up in that group, Walmartthey would have to get 41% more in value just to match Berkshire’s market cap.

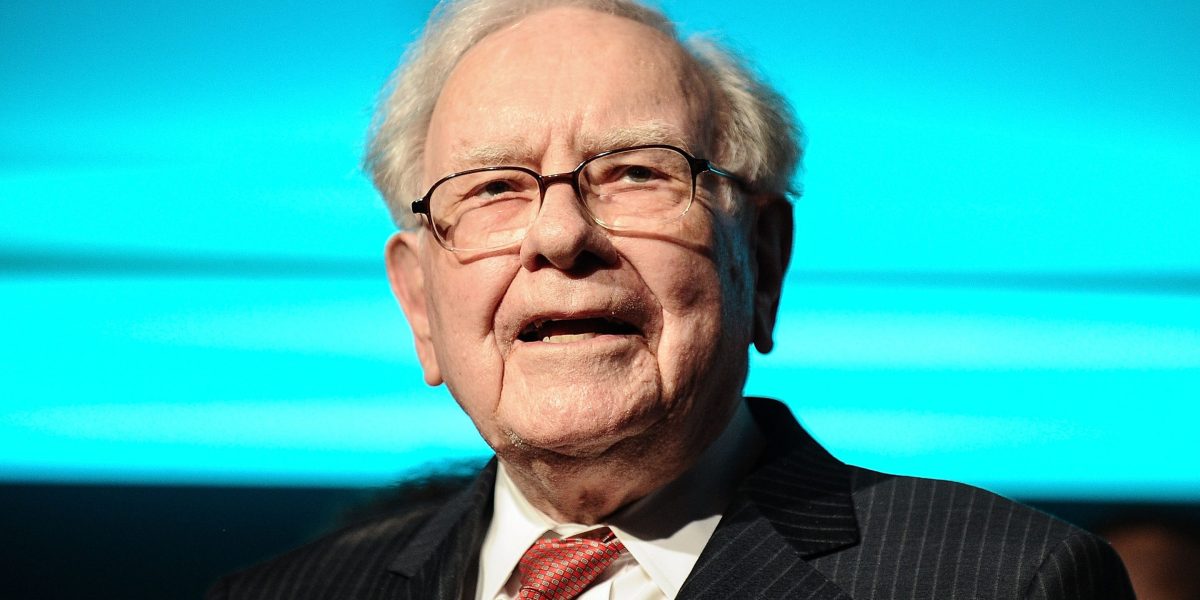

Another way to consider the magnitude of Berkshire’s achievement: So far in this tech-infatuated year, Berkshire’s stock has outperformed that of Apple, Microsoft and Alphabet. He beat the technicians Nasdaq like the S&P, Dowand the Russell 2000. It’s hard to remember CEO Warren Buffett telling his shareholders last February, “Overall, we have Not an eye-popping performance possibility.”

But then, performance can be measured in many ways, and market capitalization is not Buffett’s favorite way to value a company. Market capitalization measures market expectations, not measurable financial results, and as Buffett often notes, Mr. Market has mood swings. Buffett instead focuses on net worth calculated according to generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). The concept is simple: add up a company’s assets, then subtract its liabilities. What is left is the net worth. Apple’s net worth is $57 billion. Nvidia’s is $66 billion. Berkshire is $663 billion. Some of the other tech giants have a higher net worth than Apple and Nvidia, but none come close to half Berkshire’s. As Buffett also told investors in February, “Berkshire now has—far-the highest GAAP net worth it has recorded any American business.”

Berkshire students might object that the company is more of a tech company than it appears, since it owns a lot of Apple stock. But the argument does not hold up. Berkshire owns several insurance companies (the most famous being Geico) and invests customer premiums in huge stock portfolios—with Apple being its largest holding. But Berkshire has been offloading its Apple stock for nearly a year, with about 70% of its holdings up until now. That is, Berkshire’s stock is rising as the company exits tech, shedding its Apple stock and reaping enormous gains.

Which brings us to the decades-old secret of Berkshire’s breathtaking performance, highlighted by stock market events last year. This, of course, is no secret. That’s Buffett, the fiercely independent, fiercely intelligent CEO. He often seems out of step with the world, as when he sells Apple stock to a rising market. Other business bromides he despises:

· Everyone knows that diversified conglomerates are a terrible idea. Decades of extensive research have shown that they are not successful. But in 2015, Buffett told his shareholders: “Berkshire is now a large conglomerate that is constantly trying to expand further… If the conglomerate form is used judiciously, it is an ideal structure for maximizing long-term capital growth.” The phrase “used judiciously” is his humble way of saying “used as well as I use it.”

· CEOs don’t despise their company’s stock. But over the years, Buffett has told shareholders when he thinks Berkshire’s stock is overvalued and has warned them of potential trouble ahead, as he did this year. Berkshire is always looking for companies to buy, but it has grown so much, he said, that “there are only a few companies in this country that are capable of really moving the needle in Berkshire,” and for various reasons he is not interested in buying them. Outside the US, “there are essentially no candidates who are meaningful options.” That is why he said that the “eye-popping performance” will not happen. However, the shareholders did not run for the exit. Quite the opposite. They trust him to find a way.

· Companies promote the products they sell using them. Berkshire often does this, but not always. Sells directors and officers insurance, which indemnifies board members against personal liability for their actions. But not in Berkshire. “We do not provide (board members) directors and officers with liability insurance, which is available at almost every other large public company,” Buffett said in his 2011 letter. “If they mess with your money, they’re going to lose theirs.”

It seems mind-boggling that Buffett somehow fell into tech royalty, but it shouldn’t be. He has been fearlessly unconventional for so many years that little should surprise us. If it were otherwise, Berkshire’s stock would not have risen 4,384,748% under his 60 years of management.

Buffett never ceases to amaze. This is just his latest mind-bender: The 94-year-old CEO is joining his tech brethren and somehow outdoing them.