Unlock Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, editor of the FT, picks her favorite stories in this weekly newsletter.

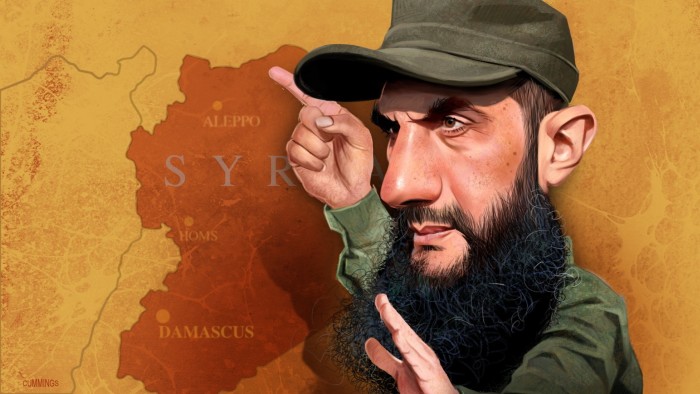

Dressed head to toe in khaki and surrounded by unarmed guards, Abu Mohammad al-Jolani triumphantly climbed the steps of Aleppo’s medieval citadel this week. The leader of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) was swarmed by supporters waving the flags synonymous with the rebel group, which had just captured Syria’s second city in a lightning offensive.

Jolani waved to stunned Aleppo residents before getting into his white jeep and driving back to the front line. He barely cracked a smile. It was a politically astute move typical of the ambitious 42-year-old Islamist who has spent the past few years in the midst of political transformation. Jolani sees himself as the future leader of Syria if his forces succeed in ousting the regime of President Bashar al-Assad.

“Jolani is very clever at choosing his moments and using them,” says Aaron Zelin, an expert on jihadism, Jolani and HTS. “He chose a symbolic place, there were no weapons – it was designed to look like a serious, political leader.”

The appearance was the culmination of a week-long offensive by HTS-led rebels, one of the most shocking moments in The bloody civil war in Syria that has been going on for 13 years and a stunning twist in a conflict whose front lines are frozen in an uncomfortable stalemate.

A few days after taking Aleppo, the rebels captured another major city, Hama, and were soon racing south towards Homs. Damascus – the capital that Jolani has long had in his sights – could be next.

The the success of the offensive highlights the fragility of Assad’s rule over his devastated country. His armed forces — despite being backed by Russia, Iran and Tehran’s proxy network — appeared to be melting away as the insurgency advanced.

It was also the product of years of careful preparation by Jolani, who helped his group recover from a near-collapse five years ago. He softened its Islamist doctrine, built up military capabilities and installed a civilian-led government.

This transformation was visible during the offensive. Jolani took advantage of his recent contact with tribes, former adversaries and minority groups, brokering surrenders and ordering minority protection. He even addressed a statement to Russia, which has helped Assad for years, suggesting that HTS and Moscow might find common ground in rebuilding Syria.

Born Ahmed Hussein al-Sharaa in 1982, Jolani spent his first seven years in Saudi Arabia, where his father worked as an oil engineer. He then moved to Damascus — the city his grandfather arrived in after the Israeli occupation of the Syrian Golan Heights.

Jolani said that he was radicalized by the second intifada in 2000. “I was 17 or 18 at the time and I started thinking about how I could fulfill my duties, defending a people who were oppressed by occupiers and conquerors,” he said. he told PBS Frontline in 2021, in one of his only interviews with Western media to date.

Drawn to resist the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, he landed in Baghdad after a long bus ride from Damascus just weeks before US forces. He spent the next few years rising through the rebel ranks before being captured and thrown into the Camp Bucca prison, now notorious for incubating a generation of jihadist leaders.

Freed just as the Syrian uprising began in 2011, Jolani crossed the border with bags full of cash and a mission to expand al-Qaeda. Many in Iraq were happy to see him go. He was at odds with al-Qaeda leaders there, and the rivalry continued to grow. Jolani distanced himself from their transnational jihadist ideology and grew his rebel faction under the umbrella of the nationalist struggle for Syria. He eventually broke away and openly fought al-Qaeda and Isis.

He also purged the more radical elements of HTS and helped create a technocratic administration. “Jolani’s fate is being written right now. How he manages the next phase, if HTS manages to remain inclusive, will determine what its legacy will be,” says Jerome Drevon, a jihad expert at the Crisis Group think tank.

Jolani stands out among his peers. He is well-educated, urbane and soft-spoken. His middle-class background “helped shape his approach to Islam,” says Drevon. “He often says that the real world has to guide your Islam, that you can’t force your Islam on the real world.”

But jihadism expert Zelin warns that this does not make Jolani a liberal democrat, describing him as a “charismatic leader of an authoritarian regime”.

This was key to his success. As well as his group of young advisors. “They are very well educated people who understand the outside world. They don’t have a bunker mentality,” says Dareen Khalifa, Drevon’s Crisis Group colleague, who has met with Jolani several times since 2019.

The question is how far can the transformation go? The US has designated HTS a terrorist organization and set a $10 million bounty on Jolani’s head — which could complicate his aspirations to build relations with the West and lead Syria.

This week, Jolani told Khalifa that his group would consider self-dissolution, that Aleppo would be governed by a transitional body and that the city’s social fabric and diversity would be respected. Whether the group can reconcile this plan with its jihadist roots remains to be seen.