Unlock Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, editor of the FT, picks her favorite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The Labor Party will not have to apply to renew its lease of power until eight months after the end of Donald Trump’s second term as US president. Or, in other words, enough time for South Korea to go from a democracy to a state of emergency for a 1,719-times-punished president to rule.

To judge the measures in Keir Starmer’s new “plan for change” according to their electoral effectiveness is therefore quite silly. It is clear that governments can do things to help their re-election prospects (such as pouring more money into the UK’s dilapidated public realm), but they can also do economically damaging things (such as funding that glut by increasing corporation tax). But the decisions made by the British state in 2024 are a relatively minor component in deciding whether British voters feel more prosperous, more secure and therefore more inclined to re-elect Labor in half a decade.

All we can say for sure is that Labour’s time in power will be limited and hampered by two pre-election blunders on tax and staff. The decision to fulfill the Conservative Party’s impossible promises to cut income tax, VAT and national insurance means both that they have less money to spend and that the money they do spend will be raised in ways that do little harm to the UK’s growth prospects. Giving the role of chief of staff and orchestrator of Labour’s preparations for government to Sue Gray, a consummate Whitehall fixer but with no relevant experience as a boss, has resulted in uneven plans and an uneasy operation in Downing Street.

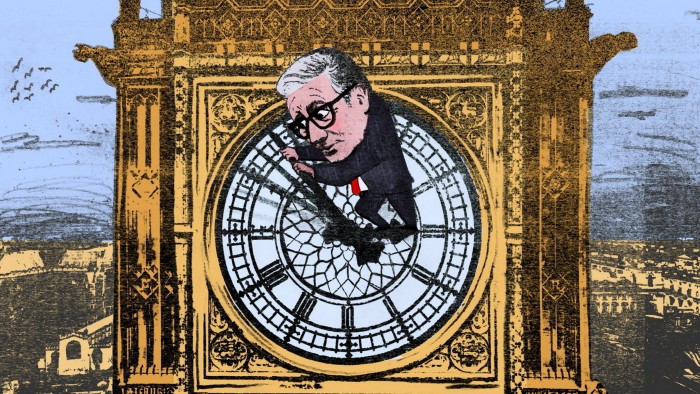

Starmer’s first term will be partly defined and limited by those mistakes and whether Labor can govern despite the negative effect of its own tax promises.

Westminster prefers to use the judgment of the electorate as its benchmark for everything for two reasons. One is that the UK has, for one reason or another, only enjoyed 18 months of stable, drama-free government since the 2016 Brexit vote. Seeing it all as a series of stage sets between the frequent electoral conflicts was a pretty good way to look at it policy almost a decade.

But another reason is that all ecosystems are shaped by their top predator. And Starmer’s own political style leads everyone, from his inner circle down, to think and talk about politics as a series of diversions between elections. His plan for change is, in essence, a promise that the UK is new Work The government will deliver on the promises Boris Johnson made but failed to keep in 2019: invest more in public services while keeping income tax, national insurance and value added tax at current levels and cutting immigration.

In many ways, this is a good thing. Keeping at least some of those promises was an urgent need when Johnson made them five years ago; half a decade of failure hasn’t made him any less so. But there is no clear logic in believing that Starmer will succeed where Johnson failed. It is not clear what incentives Starmer wants to change in Whitehall and how he will run public services differently from the Conservatives. Without a clear direction why the same promises and the same restrictions will not lead to the same outcome, everything is refracted through the prism of choices that are far away.

Starmer has always shown a willingness to reject principles and people when necessary, but the position he has maintained most strongly is institutionalism. He saw one of his first tasks as Labor leader as restoring the party’s institutional memory, which meant recruiting behind-the-scenes operators with deep ties to New Labour’s election-winning past. In office, he appointed ministers with institutional knowledge. His aides were mostly drawn from Tony Blair’s Downing Street. Chris Wormald, the new head of the civil service, is Whitehall’s longest-serving permanent secretary and a protégé of former cabinet secretary Jeremy Heywood.

Not everyone has the same policy. Starmer’s tent includes those whose institutional memory leads them to believe that all the machine needs is more money and more love, along with those who believe it needs massive amounts of reform. Downing Street’s new look embodies both worlds: Morgan McSweeney as chief of staff brings deep knowledge of fighting and winning elections and oversees a team that combines veterans from the Blair era with the structural innovations left over from Dominic Cummings’ tenure as Johnson’s chief strategist.

But Starmer doesn’t like it when ministers ask him to comment on disputes. (One minister complains that he felt “like a naughty child” because he dragged the prime minister into an interdepartmental battle). After all, its key role is to adjudicate tricky divisions between departments and interests. His team of institutionalists may be well-placed to deliver on this week’s set of refined priorities, but what’s often missing is clear political direction about what the boss really wants.

Without it, everything will still be assessed as to whether it puts Labor in the best position for the 2029 election. Ironically, this is a bad way to win the next election, as well as a bad way to run the country. The start of parliament should be when the government is obsessed with exactly what the prime minister wants it to be – not the elections that are yet to come.

I am also commenting to make you understand of the notable discovery my friend’s daughter encountered using yuor web blog. She noticed a wide variety of pieces, with the inclusion of how it is like to have an amazing helping spirit to make other folks easily learn about certain advanced issues. You actually did more than our own desires. Thanks for providing these beneficial, trustworthy, revealing and even easy thoughts on your topic to Emily.