Just five years ago, the Syrian Islamist rebel group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham was a beleaguered jihadist force struggling to survive after years of attacks by the Russian-backed Assad regime.

Now, in its stronghold in Idlib province, HTS boasts a military academy; centralized command; rapidly deployable specialized units including infantry, artillery, special operations, tanks, drones and snipers; and even the local arms manufacturing industry.

The renewed rebel group’s capabilities have been evident over the past week in its boldness raid over northern Syria which stunned observers of the country. “Over the past four, five years, it’s transformed into essentially a polished proto-military,” said Aaron Zelin, an expert on the group at the Washington Institute think-tank.

Obtaining basic weapons has been relatively easy for HTS: Syria has been awash in arms since 2011, when Turkey and Arab countries, backed by the US, flooded the country with arms to help bolster rebels in a civil war against the Iran-backed regime.

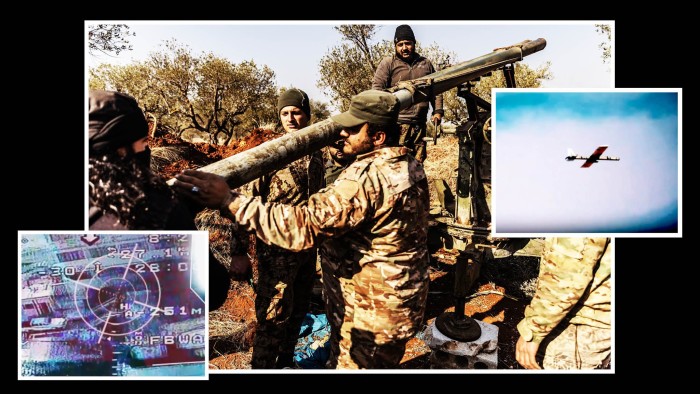

But HTS’s domestic production, particularly of drones and missiles, has allowed it to pose new threats to a regime that lacks significant anti-drone capabilities. In the past few days, the militant group has released smooth footage of suicide drone attacks on a commanders’ meeting at a Syrian army building and another drone attack on an airbase in the central city of Hama.

Inside their fledgling breakaway mini-state, home to between 3 and 4 million people, the rebels manufacture drones in small workshops located in homes, garages or converted warehouses, relying on 3D printers when they don’t have access to parts, according to experts.

“This is a common story in today’s modern conflict: we have seen similar tactics in Azerbaijan, Ukraine and elsewhere,” said Broderick McDonald, a conflict researcher at King’s College London. Much of the expertise needed could be gleaned from online sources, analysts say.

The 2023 drone strike on the Syrian military academy in Homs, which killed at least 100 people, was a “proof of concept,” Zelin said. No one has claimed responsibility for the attack, but it is widely believed to have been carried out by HTS.

McDonald, who has been monitoring the insurgent’s use of drones this week, said the group has previously used small drones that can fly into armored vehicles and drop grenades. In their ongoing offensive, they have also used home-made rocket-propelled drones and larger models that can travel further and carry larger payloads.

They used drones to monitor and target the regime before sending fighters into battle, Zelin said. In “a first for non-state actors,” he said rebels were dropping leaflets from drones over civilian areas to encourage defections.

HTS also invested in the production of long-range missiles, rockets and mortar shells. During their offensive, the militants discovered a new guided missile system, about which little is known, but which Charles Lister of the Middle East Institute described as “a massive missile with a huge amount of ammunition on the front”. It is assumed that the missile will be called “Qaysar”.

“It replaced the need for truck suicide bombs, which (HTS) would have done five years ago,” Lister said, adding that guided missiles were fired tens of kilometers across open territory before the new offensive.

Its own weapons supplemented those taken by HTS when it disarmed other rebel groups or was captured from the regime in battle. The group’s latest advance brought more equipment: Videos on the rebels’ social media channels show seized regime military weapons and armored vehicles, including some Russian-made.

“They captured huge amounts of equipment: not only tanks and (armored personnel carriers), but also anti-aircraft systems. They have a (Russian-made) bulletproof vest and several other anti-aircraft missiles that they’ve captured, as well as multiple light attack aircraft, which they’re trying to figure out how to use,” McDonald said.

“If they can get (the air defense systems) operational, it would alleviate one of the big challenges that HTS and other rebel groups have always faced, the lack of defense against Russian airstrikes,” he said.

In recent years, researchers have observed a successful trade in arms and ammunition between regime forces and HTS on the black market.

Experts insist that Turkey, the main sponsor of other rebel factions under the umbrella of the Syrian National Army, does not supply HTS directly. Ankara, along with the US and other countries, has labeled the Islamist movement a terrorist organization. But some of HTS’s current supplies have been supplied by Ankara-backed rebel groups in northwestern Syria, analysts say.

HTS and some Turkish-backed rebel groups maintain close cooperation, including the current offensive, and weapons are transferred between the groups. Turkey has given the rebels Toyota 4x4s, armored vehicles and personnel carriers, “usually used Turkish stuff that is out of use in the Turkish army,” said Malik Malik al-Abdeh, a Syrian analyst.

This equipment is used by a group with a very different structure from four years ago. When HTS accepted a ceasefire brokered by Turkey and Russia in 2020, it used the ensuing period of relative stability to reevaluate its strategy and military doctrine.

By then, HTS had to some extent mimicked the structure of the Syrian army, just as it had also reproduced civilian institutions such as the courts in Idlib, said Dareen Khalifa, an HTS expert at the Crisis Group think tank. Then, she said, the group realized that the approach relied on resources and large groups of recruits that HTS did not have.

Instead, according to Jerome Drevon, an expert on jihad at the Crisis Group think-tank, “they drew inspiration from Western military doctrines”.

They were particularly looking at the British armed forces, which are smaller and more agile, Drevon said as told by the group leader and the military commander.

HTS could call on about 30,000 fighters, experts said: 15,000 full-time fighters and several thousand reservists, as well as people from other armed opposition groups in its network of allies. The group’s rapid advance across Syria’s north would prompt even more to join, they said.

The diversity of fighters was key to the successful turnaround of the group. After President Bashar al-Assad brutally put down a mass uprising in 2011 that turned into civil war, rebel groups became balkanized, turning the country into a patchwork of rival fiefdoms. At the time, HTS was a group of several dozen hardened jihadists, an offshoot of al-Nusra, a jihadist force created in the chaos of war.

HTS eventually absorbed some surviving rivals. Its ranks have swelled to include foreigners and jihadist veterans from other conflicts in the region, as well as less ideological insurgents.

Fighters now had to be ideologically coherent, Drevon said, and better coordinated on the battlefield. To achieve this, HTS established its military academy about two and a half years ago. Regime defectors and foreign jihadists appear to have played a key role.

HTS convinced about 30 former regime army officers, who had defected to other rebel groups, to establish the academy, Drevon said. They replicated the regime’s military service, establishing nine-month training divided into three-month steps of basic, intermediate and advanced.

The graduates also learned behavioral discipline, said Khalifa, who highlighted the drastic differences between HTS’s takeover of Idlib province in 2015 and today.

In 2015, the group was brutal in its approach to Idlib residents, forcing them to choose between death or repentance for their perceived sins. But after dropping ties with al-Qaida the following year, while retaining authoritarian tendencies, HTS is now seeking to publicly show tolerance towards religious minorities. He has allowed Christians to lead Masses in churches in Aleppo since taking control, according to images on social media, of the local bishop and the group itself.

The group also showed discipline on social media, displaying almost total silence to ensure an element of surprise for Assad’s forces, Lister said.

McDonald said some of the group’s special forces “went into Aleppo the night before HTS attacked the city last Wednesday, and they reportedly targeted regime officers.”

The rebel advance on the capital Hama, which has remained in regime hands during 13 years of brutal civil war, has highlighted the weakness of the Syrian army and pro-regime militias, which — despite being backed by forces from Russia, Iran and Tehran’s proxy network — have abandoned their positions in fear of the advance of the rebels.

“HTS has come a long way in five years,” Drevon said. “Now we have to wait and see where it goes from here.”

Additional reporting by Richard Salame in Beirut

Weapon illustrations by Bob Haslett and cartography by Steven Bernard